|

Thursday, April 22, 2010

Last weekend the Maryland Opera Studio premiered a new American opera, Shadowboxer,

by composer Frank

Proto and librettist John Chenault.

The work, heard on Sunday

afternoon at the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, is based on the

life of boxing legend Joe Louis, world heavyweight champion from 1937 to

1949. The opera was the brainchild of Leon Major, director of the Opera

Studio, who kicked around the idea for over twenty-five years before

finding a composer and librettist to do the work. Proto and Chenault

were suggested to him by fellow University of Maryland faculty member,

soprano Carmen Balthrop. Proto has written extensively for orchestra and

is equally well-versed in both “classical” and jazz styles,

and it seemed fitting to include jazz in such a quintessentially

American work. Although neither Proto nor Chenault had written an opera

before, although they had collaborated together on other projects. Both

were drawn to the idea of an opera about Joe Louis, particularly

Chenault, a lifelong boxing fan.

The opera depicts the final

moments of Louis’s life, when he relives his entire career through

a series of flashbacks. He is portrayed by three different actors: as a

wheelchair-bound old man on the verge of death who remains on stage

throughout the opera, reflecting on the events taking place; as the

younger Joe Louis interacting with other characters as his life

progresses; and as the fighter in the ring whenever fights are shown (a

non-singing role, always in a choreographed fight against the same

opponent). Characters surrounding Louis are his wife, his mother, agents

and trainers, a trio of newsmen (either nay-sayers or supporters,

depending on which way the wind is blowing), a trio of

“beauties” who seduce Louis (later on appearing as nurses),

and a ring announcer.

Louis’s eventful personal life

plays out against the historical backdrops of the Great Depression, Jim

Crow era segregation, and World War II. Consequently,

Shadowboxer deals with a number of different themes: the racism

Louis endured as the first African American sports hero; his patriotism

and defense of American democracy and freedom during World War II in

spite of being treated as a second-class citizen; his courage, honesty,

integrity, and “clean” approach to the sport; his generosity

and subsequent financial difficulties, especially with the IRS; his

relationships with his mother, Lillie, and his wife, Marva; his weakness

for women; the drug addiction and mental illness that plagued him at the

end of his life.

A pivotal moment in both Joe Louis’s

life and the opera was his first defeat in the ring, at the hands of Max

Schmeling of Nazi Germany. Two years later, Louis came back to fight

Schmeling again, this time knocking him out in just two minutes and four

seconds and regaining the world title. To much of the world, this

victory symbolized the triumph of American democracy over German

fascism.

According to Chenault, the title

Shadowboxer has two implications: first, in Chenault’s

words, “the image of Louis confronting his own mortality in an

epic struggle with death;” second, as a metaphor for Louis’s

position in the history of boxing between his predecessor, Jack Johnson,

and his successor, Muhammad Ali, whose career overshadowed

Louis’s. This is brought out towards the end of the opera when a

solo on-stage saxophone and trumpet portray Johnson and Ali, with their

words projected on the screens. However, there are other allusions to

the concept of a “shadowboxer” throughout the opera:

taunting Louis before their second fight, Max Schmeling calls him a

shadowboxer. (Ironically, in real life, but not in the opera, Louis and

Schmeling became good friends in later years.) When representing the

U.S. during World War II, Louis laments that he is “a symbol, not

a man.” When Louis can’t seem to stop his womanizing, his

wife Marva complains that he has become a shadow and says “I love

the man who isn’t there.”

With so

much story line, there is plenty of drama and multiple layers of meaning

which both the libretto and the music express effectively. The work is

scored for a 44-piece orchestra in the pit and an 8-piece jazz band at

the back of the stage; the orchestral and jazz portions blend seamlessly

together, creating a lush musical tapestry supporting the singers in

their wide ranges of emotional expression. Conductor Timothy Long drew

superb performances from the musicians, members of the University of

Maryland Symphony Orchestra and Jazz Studies Program, as well as the

fifteen opera soloists and twelve-member chorus. That the voices were

always audible above the orchestra is a tribute to both the composer and

the conductor. The singers’ clear diction and the supertitles

displayed on large monitors at the sides of the theater made it easy to

understand the text.

Erhard Rom’s scenic design is

simple but powerful. At the back and sides of the stage are three large

screens, onto which vintage black-and-white images were projected:

boxing scenes, posters, and news headlines, as well as various World War

II photographs. Aside from that, the only props are chairs and the masks

worn throughout much of the opera by cast and chorus members. The

costumes, designed by David Roberts, are period suits and dresses in

various shades of gray; the only colored object on the stage is the

elderly Joe Louis’s bathrobe.

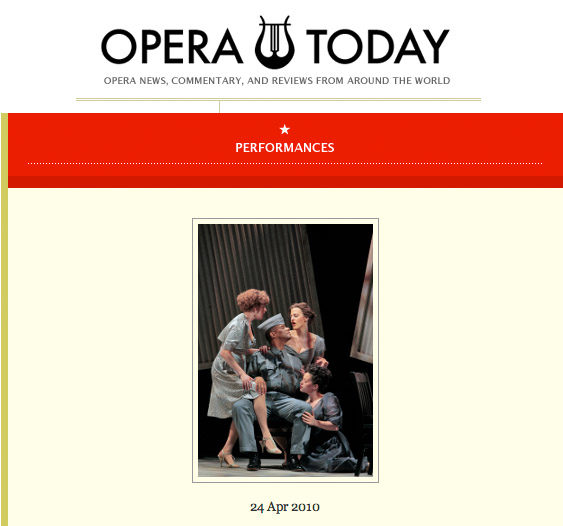

Outstanding performances

were delivered by the entire cast, in particular Jarrod Lee and Duane A.

Moody as old and young Joe Louis, respectively, and Adrienne Webster as

Louis’s wife, Marva Trotter. Not surprisingly, the most stunning

performance was by Carmen Balthrop in the role of Louis’s mother,

Lillie Brooks. Leon Major’s brilliant staging communicated the

depth inherent in the score and libretto. Shadowboxer is a

complex and profound tour de force which is highly deserving of future

productions, and the Maryland Opera Studio is to be commended for

commissioning it. Anyone interested in contemporary American opera

should take advantage of the remaining performances scheduled for April 23 and

25.

Janet Peachy

Ionarts

While the Dresser has done things like played lacrosse for a semester in college, donned the white jacket to fence, and participated in endless games of murder ball, she has never been into the martial arts and certainly not boxing. Therefore, what would she think of an opera based on Joe Louis, the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1937 to 1949? On April 18, 2010, the Dresser heard and saw Shadowboxer, an impressive world premiere at the University of Maryland's Clarisse Smith Performing Arts Center. The work is by composer Frank Proto and librettist John Chenault. under the stage direction of Leon Major and baton of conductor Timothy Long.

THE BROWN BOMBER FROM HIS WHEELCHAIR

Chenault anchors his poetic libretto about the larger-than-life boxer, nicknamed "the brown bomber," through the memories of a sick old man confined to a wheelchair--Louis at the end of his life and now a shadow boxer fending off the ghosts of his former days. The audience learns that Louis came into the ring with stringent rules that helped promote him as a clean-living and honest fighter, who did not gloat over a fallen opponent. While Champion Louis did not smoke, drink, or do drugs, he was frequently seen in the company of white women despite having a loving wife and supportive mother. His fights with the German boxer Max Schmeling put the eyes of the Nation on him as a political warrior against the Nazi government. However, Louis's military service demonstrated that the people of the United States were still racially prejudiced. By the end of Louis's life, his wife Marva had divorced him twice (Louis was married four times though that is not brought out in the opera), he was in serious debt to the Internal Revenue Service, and he had a severe problem with hardcore drugs like cocaine.CLASSICAL WITH JAZZ

Frank Proto creates a large classical soundscape for Shadowboxer. His music is complex and has accents that remind the Dresser of Benjamin Britten in Britten's less melodious moments. As a counterbalance to this classical schema played by 41 pit musicians, Proto positions eight jazz musicians on stage with the 15 cast members and twelve choral singers. The jazz occasionally breaks through in numbers like one sung by Louis's mother Lillie.

DON'T KILL HIM

The voice of Soprano Carmen Balthrop (Lillie) interrupts Louis's first fight with Max Schmeling (Louis loses) with profound emotional weight--"Don't kill him," she pleads. Although bass baritone Jarrod Lee as old Joe and tenor Duane A. Moody as young Joe perform credibly, the star of this production is undeniably Carmen Balthrop who understands the nuances of Proto's music. Mezzo-soprano Adrienne Webster as Marva, especially in duet with Balthrop ("a dream of Sunday punches") provides a strong performance.

Adding to the large scale of Shadowboxer are Erhard Rom's minimalist set design and Kirby Malone and Gail Scott White's projection design. One particularly powerful scene occurs when Louis has his second fight with Schmeling. The projections on three screens of Nazi soldiers in combination with the cast sitting in many rows of chairs heighten the tension of the fight. By the way, there is a third performer (non-singing role) Nickolas Vaughan who plays Joe, the boxer. The slow motion choreography works well to portray the fight scenes within the context of old Joe's memory. Leon Major has drawn together an top notch team to present this opera.

Major also uses masks on the players that surround Louis. Why Major chooses to do this is not entirely clear to the Dresser but the most effective use are the black sambo masks used when Louis appears in his soldier's uniform. This clearly serves to heighten the racial isolation and hounding Louis suffers.

There was one thing the Dresser puzzled over and that was who was the female singer who ends the story of Joe Louis's life. However, in a talkback session that followed this performance, the Dresser posed the question and also asked why couldn't that person be the three reporters (played ably by tenor Andrew Owens, baritone Andrew McLaughlin, and baritone Colin Michael Brush) or Louis's mother Lillie? Much to the Dresser's surprise, Leon Major said that was a good question and although the idea for that role involved call and response by an unknown character, the part clearly should have been played by Louis's mother. Leon Major said it had not occurred to him and that his oversight was a mistake. The Dresser says in the next production, which should be by a large opera company, there will be ample opportunity to tweak such things.

Karren LaLonde Alenier

The Dressing

Modern or traditional, opera loves to enact the extremes of fortune. It lusts after those great explosions of talent and energy that produce victory in war or love. It adores, just as much, the lingering decline that questions a life's meaning. History and audiences have taught opera to seek out the grandes grandeur and the saddest sadness.

The story of Joe Louis, a great boxer, perhaps the greatest of them all, provides the perfect subject. The University of Maryland Opera Studio has made his life the centre of its recent project, Shadowboxer: An Opera Based on the Life of Joe Louis, with music by Frank Proto, libretto by John Chenault -- and an idea that was born long ago in Canada. In the 1930s and 1940s, when boxing was so popular that a major fight could draw 70,000 spectators to Yankee Stadium and just about everyone knew the name of the world heavyweight champion, Joe Louis was the most admired boxer in the world. He was (the great sportswriter A.J. Liebling wrote) the most conspicuous ornament of his profession, "the highest feather in its hat." More than anyone else, he brought boxing back to honest prominence and prosperity after the dark days of corruption that followed the Jack Dempsey era.

Among blacks Louis became the ultimate ethnic hero. Langston Hughes, the poet of the Harlem Renaissance, wrote that "No one else in the United States has ever had such an effect on Negro emotions--or on mine. I marched and cheered and yelled and cried, too."

At age 23 Louis became the youngest heavyweight champion in history and soon found himself adopted as the first black man ever embraced by a large mass of Americans, the Tiger Woods of his time. Better still, his most famous bout became a legendary moment in world history, a propaganda triumph in democracy's struggle against Nazi Germany.

Shadowboxer makes an ambitious, stirring and often surprising evening at the University's theatre at College Park, MD. The productions it gets in future will determine its place in American music but it's already marked itself as unique: How many operas bring together sports, politics, mass culture and race within the musical context of a jazz band and a full standard orchestra plus chorus and three huge movie screens? How many use the ancient art of radio as a sound track for the climactic scene?

That scene would have to be, as anyone of a certain age will guess, the second Schmeling fight. On two occasions Louis fought Max Schmeling, Germany's finest heavyweight and one of the world's best. Schmeling won the first bout in 1936, knocking out Louis in the 12th round, giving him his first professional defeat.

But that was just a boxing match. Their second fight, in 1938, turned into an epic struggle between civilizations. In Nazi Germany the newspapers painted Schmeling as the Third Reich's single-combat warrior, an Aryan superman who couldn't be beaten by a subhuman black. In the U.S. and elsewhere, Louis became democracy's champion.

For the supporters of Louis, the victory was almost too swift. He knocked out Schmeling two minutes and four seconds after the first round began. Across the U.S., thousands of blacks poured into the streets to celebrate. Louis's place in the history of African-Americans, as well as in the history of sport, was fixed forever. "I knew I had to get Schmeling good," Louis said later. "I had my own personal reasons and the whole damned country was depending on me." Strange as it may seem, that was not an overstatement.

In Toronto that fight became a family legend for Leon Major, who grew up to be a director of theatres in Halifax and Toronto and then moved to the U.S. to direct and teach opera. Family lore has it that Leon's father, before settling down to hear the radio broadcast, went to the kitchen for a glass of tea. By the time he returned to the living room radio, the fight was over. Both the speed and the social resonance of that victory impressed Leon.

Eventually he decided Louis carried the seeds of an opera. He pursued the idea over decades, commissioned it and has now directed the first production, before enthusiastic audiences. Shadowboxer frames the story by having Louis, age 66 and dying, sitting in a wheelchair in his bathrobe as he dwells on the calamities and successes of his life. Sometimes he remembers the truth, but sometimes paranoid fantasies distort his memory. In his feverish moments Jack Johnson, the earlier black champion, and Mohammed Ali, a later generation's star, visit him. He has much to regret, including drugs and troubled relations with women. His relations with the federal government plague him to the very end. Has any previous opera cited the Internal Revenue Service as a major nemesis of a heroic life? Like many boxers, Louis struggled with greedy managers and ended up with a seven-figure IRS bill he apparently didn't quite understand.

By the time Joe's mind turns to the second Schmeling fight, we have already seen other fights depicted. Major, being a child of the radio age, audaciously depicts this central event by running a tape of the original broadcast. The excitement of the 1938 play-by-play announcer pours out of the sound system while Jarrod Lee, a student who sings the part of Old Joe with astonishing effectiveness, acts out the fight on an otherwise empty stage. The combination brings the moment alive in a dazzling mix of power and pathos.

To tell this complicated story, Shadowboxer deploys film, still photo, masks and stylized, slow-motion movement. At one point, when we reach a painful defeat in Louis's declining days, we watch the essence of a fight depicted simply in two shadows fighting behind a screen.

This university account of a legendary career combines documentary history with a melancholy salute to a long-ago titan and an interior monologue in which a tortured hero anxiously searches his soul and at the end finds it wanting. But audiences in the age of Obama may decide that Shadowboxer touches them most deeply when they contemplate talented young black singers in their mid-twenties recreating the atmosphere of pre-Civil Rights America, a time that the young know mainly as a horror story told by their grandparents.

Robert Fulford

Financial Post (Canada)

From the Maryland Opera Studio comes a riveting new opera that transforms the life of American boxing legend Joe Louis ("The Brown Bomber") into an epic tale of human struggle, triumph, and failure.

Directed by Leon Major and authored by librettist John Chenault and composer Frank Proto, this work will capture the imagination of opera lovers and sports fans alike.

Shadowboxer tells the story of Joe Louis, the African-American boxing legend who held the heavyweight boxing title from 1937 until 1949. Despite widespread racism in the United States during this period, Louis became a national hero. In his fights against German boxer Max Schmelling in particular, Louis's life in the ring came to symbolize the larger political struggle between democracy and Nazism that was central to World War II. Thus many Americans tuned in to Louis's fights in hopes that his victory in the ring could also signal a political and ideological victory for America and the Allies. His story came to symbolize something greater than one man's journey, and the far-reaching significance of his life was what first captured the imagination of Maryland Opera Studio's Artistic Director Leon Major.

Ask Major about the genesis of Shadowboxer, and he will inevitably recount his childhood memories of the famous 1938 rematch between Louis and Schmelling, during which Louis scored a knockout in the first round. Thus his fascination with Louis dates back many years. In fact, Major had been toying with the idea of an opera based upon the life of Louis for over two decades before approaching John Chenault and Frank Proto. Their creative collaboration spanned a period of roughly two years, and culminated with a series of performances at the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center that began on April 17th and runs through April 25th.

Though Shadowboxer is based upon the life of a boxing legend, it is not confined to the boxing ring. Rather, it is a psychological drama that takes place in the landscape of Joe Louis's mind. During the final moments of his life at his Las Vegas home, an elderly Louis is forced to confront a barrage of vivid and painful memories that become increasingly fragmented and incoherent as death draws near. The opera is a portrait of Louis's final moments and the nightmarish fantasies that he must grapple with as he reflects upon his trials, triumphs, and failures. Chenault transforms the life of this American hero into a sweeping tale of human struggle, victory and defeat, suffering and joy.

The musical score of Shadowboxer is equally broad in its scope. Frank Proto drew upon his decades of experience as a composer and performer of classical music, jazz, and even Broadway show tunes to create a musical language that is as multifaceted as his musical background. Far from being a stylistic hodgepodge, however, Proto's score captures the phantasmagoric nature of Louis's consciousness and is an apt musical counterpart to the drama onstage. Shifting between a dissonant 21st-century idiom and a jazz-infused style that draws inspiration from American popular music of the 1930s and 40s, Proto's score reflects the sounds of Louis's heyday as they would be remembered in the murky recesses of the boxer's deteriorating mind. Under the direction of conductor Timothy Long, the singers and instrumentalists of the University of Maryland give a compelling performance of Proto's imaginative score.

The opera's intriguing storyline and music should be enough to arouse curiosity in most music and sports lovers, but for those who are still not inspired to swing by the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center this weekend, Major's staging of the production should provide further incentive. Major does not simply approach Shadowboxer using a traditional arsenal of production tools. Rather, he considers how the cinematic and visual "literacy" of today's audience members make them particularly receptive to the use of multimedia technologies in the performing arts, and he incorporates those technologies with a discerning eye. Multimedia designers Kirby Malone and Gail Scott White join forces with scenic designer Erhard Rom, lighting designer Nancy Schertler, and costume designer David Roberts to create a synthesis between classic production techniques and modern technologies.

Rom's deconstructed stage design functions as the ideal backdrop for Schertler's expressive lighting, which is used to convey the variegated landscape of Joe's mind. At times, Schertler spatters the stage with dispersed beams of light and shadow, which serve as a visual counterpart to Louis's fractured memory. During other scenes, she envelops the stage in suffocating ashen shades that - combined with grey costumes and a choir of masked faces––project Louis's isolation and confusion as he sifts through hazy memories and painful emotions. Especially memorable is the scene in which Louis's wife Marva sings her heart-wrenching aria "I love the man who isn't there" immediately after handing her husband divorce papers. Schertler captures the mental anguish of both characters by bathing the stage in an eerie red glow. As Marva sings over martial rhythms played by the orchestra, her towering shadow looms above Louis, a devastating reminder of the torment he caused her by his womanizing lifestyle.

The asymmetric shapes and contoured screens of Rom's stage design also pair well with the digital projections of Malone and Scott White. Avoiding naturalistic backdrops in favor of expressive abstractions, Malone and Scott White create a living world of action onstage. Their projections function as settings, dreamscapes, and reflections of Louis's mind. Cloudy images of black and white shadows communicate Louis's mental confusion and muddled memory, whereas projected details of the boxing ring set the scene, without suggesting a concrete reality. Photographs and newspaper headlines from Louis's fights in the years leading up to World War II are juxtaposed with scenes of the raging war in Europe, thereby indicating how his victories in the ring were perceived as political and ideological triumphs. In this manner, the projections become characters in their own right, commenting upon the action and communicating the far-reaching implications of Louis's life in the ring.

Such incorporation of modern technologies in opera is likely to make most traditionalists uneasy, but Malone and Scott White leave no doubt as to their artistic integrity. Their incorporation of new media not only enhances the psychological drama onstage, but also helps to make the production contemporary and relevant to a 21st-century audience.

Finally, we turn our attention to those artists who breathe life into the score and libretto of Shadowboxer, the performers themselves. Composed primarily of singers from the Maryland Opera Studio, this cast of performers includes many vocalists who will likely have successful singing careers upon leaving the University of Maryland. This is certainly true of Jarrod Lee, whose portrayal of old Joe Louis is, without a doubt, the highlight of the show. With a rich baritone voice that seems to glide effortlessly through even the most demanding passages, Lee gives a performance that is both musically refined and poignantly acted. His sensitive portrayal of Louis is the crux of the show's effectiveness as a psychological drama. University of Maryland faculty member Carmen Balthrop also gives a captivating performance and nearly steals the show with her stirring portrayal of Louis's mother. Also noteworthy are Adrienne Webster (Marva Trotter, Louis's wife) and VaShawn McIlwain (Jack Blackburn, Louis's trainer), whose impressive vocal abilities are matched by their talent for dramatization. Less impressive is Duane Moody's portrayal of young Joe Louis. Moody does not convincingly project the youthful vigor and tenacity of the heavyweight boxer. Furthermore, his performance emphasizes the boxing champion's vices, but fails to effectively communicate his dignity and humanity.

In spite of this single shortcoming, Shadowboxer is well worth the trip to College Park, and one can only hope that its premiere at the University of Maryland will inspire future performances. In an era when opera must compete with mass consumerism and digital technologies, it is refreshing to see a new work that merges the performing arts with new media, and that explores timeless themes in more contemporary contexts.

Kate Weber-Petrova

University of Maryland

When stage director Leon Major was a little boy, his father was eager to listen to the boxing match between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling. Louis was the defending heavyweight champion, Schmeling was a representative of Hitler's Germany who had beaten Louis two years before, and their rematch in June 1938 was one of the most anticipated fights of all time, for its political as well as for its athletic significance. "My father, who was a tailor in the shtetl, wanted to hear that Joe Louis fight," Major says. "I don't think they have boxing in the shtetl." When the fight started, "my father went into the kitchen to get a glass of tea," Major says. "And when he came back, the fight was over." Louis knocked out Schmeling in 2 minutes 4 seconds.

Major is now the artistic director of the Maryland Opera Studio. For 25 years, he has been thinking about an opera based on the life of Joe Louis: good vs. evil in the age of the Nazis, black vs. white in the age of Jim Crow and, finally, a fallen hero when Rocky Marciano knocked him out in 1951 and then apologized to him backstage: "I had to do it, Joe." That opera, finally, has come to pass. On Saturday night, "Shadowboxer," by Frank Proto and John Chenault, with Major directing, is opening at the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center on the University of Maryland campus in College Park.

There haven't been a lot of operas about boxing, and yet there are certain parallels between the two sports, or arts. "It's the same crowd and the same lights," pointed out Jack Johnson, the first black holder of the heavyweight title, after making his opera debut in 1936 in the nonspeaking role of a captive Ethiopian general in Verdi's "Aida."

There's also the same athletic element: Opera, too, is a physical feat, the result of long years of training brought to bear on a few key minutes at center stage while the expectant crowd roars for blood. The one-on-one drama of single combat in boxing certainly has a theatrical aspect. Major has been working on developing the parallel; his cast worked out with the university's Terps Boxing Club.

What does the music of boxing sound like? Carmen Balthrop, a soprano and voice teacher at the university (and the only faculty member in the "Shadowboxer" cast) introduced Major to Proto, a double-bass player and composer who is equally at home in the worlds of classical music and jazz.

"Jazz has always been part of my life," says Proto, who played with the Cincinnati Symphony for more than 30 years but has also written for and performed with the likes of Duke Ellington and Dave Brubeck. Self-taught as a composer, Proto -- who has done six previous works with Chenault, a professor of African American studies -- doesn't restrict himself to specific genres. He thought jazz should be a part of "Shadowboxer," too, and he's put an eight-member jazz band onstage, along with a more conventional orchestra in the pit.

"Most of the kids don't realize it's hard," Proto says of the student orchestra. "They just do it." He spoke of working with one classically trained percussionist who was starting to feel the groove: "As we go along," he said, "he's been getting nervier and nervier." At one point, the lead alto sax has to play along with an aria for the character Marva. "He's 19 years old," says the 68-year-old Proto. "Like my grandchild. The aria has some very seductive phrases, and I told him to, 'Get more sexy.' He must have been wondering who is this dirty old man was."

Another parallel between opera and boxing is the speed of the actual event. New opera productions only have a few performances -- "Shadowboxer" runs through April 25 -- and seldom get a second hearing, though one always hopes. Major is familiar with the process; "Shadowboxer" is his third commission for the Maryland Opera Studio, after "Clara" and "Later the Same Evening." Neither has been heard again.

"It's really very strange," he says. "It's unreal. Here we are we've been thinking about it for 15 or 20 years, and rehearsing it for what seems like forever. Now it's about to open, and in a week and a half it will be gone."

Anne Midgette

Washington Post Staff Writer

If you tried to write down two words that most people would never expect to see together, it would be difficult to top these: opera and boxing.

The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center at the University of Maryland, College Park, will bring those two disparate worlds together Saturday when 78 singers and musicians stage the world premiere of "Shadowboxer," an opera about the life of Joe Louis, the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1937 to 1949.

"My first thought was, ‘Why hasn't someone done this before?' " said John Chenault, who wrote the libretto for "Shadowboxer." "It seemed such a natural subject for an opera."

Leon Major, the director of the Maryland Opera Studio at the College Park school, was a 5-year-old living in Toronto on the night of June 22, 1938, when his father - just like many people around the world - turned the radio on to listen to the rematch with Max Schmeling of Germany for Louis' world heavyweight boxing championship.

Schmeling had given Louis his only defeat to that point, and the rematch had taken on epic proportions at the dawn of World War II. The Nazi media machine proclaimed that no black man could ever defeat a true Aryan man such as Schmeling.

"He turned the radio on to hear the fight; in the middle of the first round, he went into the kitchen to get some tea, and when he came back the fight was over," Major said of his father.

Louis knocked Schmeling down three times in that first round, and on the third time, Schmeling's trainer threw in the towel, ending the fight and handing the world title to Louis. He held that championship for 12 years, one of the reasons the International Boxing Research Organization ranked Louis the No. 1 boxer in history in 2005, ahead of Muhammad Ali, Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey and Rocky Marciano.

Major cannot remember if he was there with his father that night or if it was just a story told to him by his family, but it remains part of his memories. That, and other events in Louis' life while he was growing up, "stuck with me," Major said."When I moved from theater to opera, the idea of having an opera about Louis started to take hold," Major said.

An opera focusing on a major American historical figure fits in with modern trends, according to a director who is not part of the "Shadowboxer" production. "For the last 25 years, librettists and composers have been challenged to tell the American story with the depth that opera provides," said Garnett Bruce, who serves on the directing faculty at the Peabody Conservancy in Baltimore. "What is new is that ["Shadowboxer" is] not about celebrating the great moments, but taking a look at the downfall." Indeed, "Shadowboxer" opens with Louis having the heart attack that would cause his death in 1981. It also includes flashbacks to some of the low points of his life, including drug addiction, his three marriages and a mental breakdown.

"I wanted to start [with the heart attack]," said Chenault, the librettist. "I really wanted to get to the interior of his life, because he had such a public persona and a heavily managed career. ... Start at the end, and work through his mind and his memories." Chenault said Louis was carefully managed because he was the first prominent African-American sports figure since flamboyant boxer Jack Johnson, who was controversial because of his boastful nature and his habit of consorting with white women.

Major handed his idea for a Joe Louis opera to a team that had never composed one: Chenault and composer Frank Proto, who have been working together since 1993. Proto has a background in both jazz and classical music. Jazz plays a prominent role in "Shadowboxer." Major and Bruce both said that, as far as they know, this will be the first opera in history to include a full jazz band on the stage. "The music is unlike anything I've seen before," said Timothy Long, who is the conductor for the opera. "When Leon told me that a jazz band would be involved, I'd never heard anything like that."

"For a composer, this is the pinnacle," Proto said of doing an opera. Proto was the composer in residence for the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra for 25 years and said he has often written 70-minute compositions that required weeks of work. But nothing prepared him for writing an opera. "I would give the orchestra the music, we would rehearse for a couple of weeks, and then they would play it flawlessly on a Saturday night," Proto said. "For an opera, on the other hand, not only do you have the music, but lights and projections and everything. "Right now I'm sitting in on the tech queues, and they're working out the lighting and the slides that appear on the screens onstage. They are up to 43, and we're still in the first act. The choreographer just tapped me on the shoulder and asked if I would like to see the choreography for the first Louis-Schmeling fight. It's beautiful. There's just so much more that goes into this, and at this point, it's out of the composer's hands."

The role of Louis will be played by two men. Jarrod Lee plays the older Louis, and Duane Moody is the younger Louis seen in flashbacks. "This is hard music," said Lee, a bass-baritone.Lee has only been pursuing opera since 2005 and was originally cast as Louis' manager. "Then, Leon asked would I be interested in being Joe Louis," Lee said. "My mouth just dropped, I was shocked."

Bringing a new opera to life takes time and many revisions. Lee said they did their first read-through for this opera in January 2009, and they have been working through it ever since. Proto said they were still making changes a week before the show. "That's one of the great advantages of opening at a university setting," said Bruce, the opera director. "You can take the time to experiment and fine tune. You also don't have the pressure of an international opera opener that they might have at the Los Angeles Opera or The Met in New York."

"I think it's going to be one terrific show," Major said. "Musically, it's exciting, with the jazz and the orchestra in the pit. People will be interested in this story. It is through Jim Crowe America, it's pre-Civil Rights, so it was a violent time, and there are scenes in this opera that are very disturbing. And they're disturbing ‘cause they're real."

Ken Sain

Staff Writer

Shadowboxer - The Inner Life of Joe Louis An opera about boxer Joe Louis might seem like a futile undertaking: according to 1930s New York Times reporter Meyer Berger, "Joe Louis avoids meeting people, hates conversation (even fight talk) and says less than any man in sports . . ."

Despite the countless articles on Louis's life and career that appeared in newspaper sports pages and gossip columns of the 1930s through the 50s, his 1978 autobiography, My Life, was the only public statement the boxer ever made about his personal life. The nature of opera is to delve into human psyche, but we know so little about Joe's innermost thoughts and feelings — how could it be possible to write an opera about one of organized sports' most notoriously silent figures?

Composer Frank Proto, librettist John Chenault, and director Leon Major struck out to do just that. Shadowboxer is an opera that addresses the issues of racial stereotyping and segregation, the blessing and curse of modern celebrity, and one man's struggle to overcome his inner demons to become a hero to millions of his fellow Americans. As an elderly Louis (a role split between Jarrod Lee as Old Joe, Duane Moody as his younger self, and Nickolas Vaughn as Joe the Boxer) looks back on his life, he remembers both the tragedies and triumphs he experienced as an African-American in a sport dominated by white athletes. The opera is comprised of flashbacks that occur in Old Joe's mind, and many of these memories bleed into the character's reality. These trips down memory lane focus on the boxer's early career, Joe's marriage to Marva Trotter (Adrienne Webster), and his famous bout with German boxer Max Schmeling (Peter Burroughs). Shadowboxer chronicles Joe's philanthropic contributions to the US armed forces during WWII, the discrimination he experienced during his enlistment in the US Army, and his financial ruin at the hands of the Internal Revenue Service. The opera fast-forwards to Louis's descent into substance abuse and madness and the revival of his celebrity status in his later years. Though he led a turbulent and somewhat sad life, Joe Louis's ascension to the throne of the world heavyweight boxing championship made him a true American hero at a time when the country was firmly divided along racial lines.

Librettist Chenault sees the title Shadowboxer as having a double meaning: "[The term] Shadowboxer fits with the boxing world… but in particular reference to Joe [it makes us ask] how do we peer behind the curtain, how do we move that aside and look at the interior life of Joe?" An exploration of the mind and spirit of such a well-known but private individual is both a confining and liberating task. To interpret the factual account of a life through the medium of opera is, in some respects, liberating; through music and words, Proto and Chenault create an emotional context for historical events. On the other hand, the distillation of a real person with complex emotions into an operatic performance of a few hours is somewhat constricting. Chenault, a poet and playwright, studied Louis's autobiography, and much of his libretto comes from Joe's own words. Proto, Chenault, and Major chose to place the 1938 Louis-Schmeling fight at the center of the work and present the rest of Joe's story as an ascent to and decent from this historic event.

The music of Shadowboxer sets this work apart in the world of modern opera. Proto's inclusion of an on-stage eight-piece jazz combo in addition to the full pit orchestra is unprecedented, and he uses this ensemble to great effect. It is not uncommon for jazz to inspire operatic music – composers like Max Brand and Ernst Krenek of the German Zeitopern tradition incorporated elements of jazz and popular music into their works of the 1920s and 30s, and George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess makes use of jazz rhythms throughout its entire score. Rather than taking on a secondary role, however, jazz exists side by side with traditional operatic music in Shadowboxer. Although this work does not feature any 1930s or 40s jazz standards, Proto says its music is "descended" from the music of the time when Joe Louis was in his prime, and the onstage jazz band takes on a life separate from its counterpart in the pit.

Proto's imaginative score is a versatile vehicle for the University of Maryland Opera Studio. Featuring a cast of performers, including graduate students in the UM Opera Studio, undergraduate voice majors, Opera Studio alumni, invited guest artists, and UM faculty (Professor Carmen Balthrop is stunning in her role as Joe's mother, Lillie Brooks) Shadowboxer is accompanied by student instrumentalists. This world-class production leaves no doubt in my mind that these musicians are professionals of the highest caliber. Webster and Balthrop give outstanding vocal performances, as does VaShawn McIlwain in the role of Joe's trainer, Jack Blackburn. All of the soloists are extremely competent, although some have problems with projection. Proto's choice to add eight extra instrumentalists on stage level places them in direct competition with the singers for that sonic space, and some do no project well over the jazz combo accompaniment. While Lee's portrayal of Old Joe is beautifully acted and impeccably sung, he is sometimes overpowered by the instrumentalists. At times, the audience is forced to rely on the closed captioning shown on screens placed to the left and right of the stage to follow the dialogue. This necessity becomes distracting, and I found myself watching the screens during the scenes featuring Joe's paramours (Madeline Miskie, Amelia Davis, and Amanda Opuszynski) to catch all the words. Balance issues aside, the cast members do an excellent job communicating with the audience through their commanding stage presence. The transcendent nature of this abstract work requires performers that connect with the audience, and this group rises to the challenge.

The production of Shadowboxer exists firmly in the tradition of modern opera. The set features a deconstructed boxing ring, complete with lights and ropes strung at odd angles, and the canvas is represented by three large white screens that hang at the back of the stage. In addition to providing context for an opera about a boxer, this set provides a backdrop for the projection designs of Kirby Malone and Gail Scott White. The practice of replacing sets with projections has been widely used in modern opera productions of the past decade, but director Major had a different vision for the incorporation of this technique. Rather than illustrating Louis's life through a series of images, Malone and White's projections serve as snapshots of his memory that support the singers and provide a context for the action. The projections contribute an element of realism by weaving familiar images (like the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the Nazi occupation of Europe) in with Old Joe's abstract recollections. Projections also facilitate an imaginary exchange between Old Joe and boxing legends Muhammad Ali and Jack Johnson. Ali and Johnson are represented by a trumpet (Brent Madsen) and tenor saxophone (Anthony Bonomo), rather than singers, and their words are projected on the screen backdrops. Bonomo's and Madsen's improvised solos are masterful and compelling, but their scene still seems out of place, as it has no parallel in the rest of the work. A return to the quasi-reality of Joe's memory seems confusing after this unreal exchange. Even in an opera that takes place almost entirely in one character's head, this sequence, in my opinion, is too abstract. Overall, the UM Opera Studio has staged an excellent production. In the words of conductor Tim Long, "It's really nice to be working on a new opera...because you don't have to fit the mold of what people have done for centuries. We can create that mold." This work is a breakthrough modern opera, and hopefully future productions will follow in the footsteps of the visionary artists who created Shadowboxer.

Jessica Abbazio